Many years ago outside a CrossFit class, a woman asked an interesting question. How do you get stronger? I saw her again many years later. She had not found the answer to the question. Instead, she turned to yoga. I don’t wish such a grim fate on anyone. So, in this article, I will try to answer the question. We will talk about supercompensation, the stimuli-recovery-adaptation curve, progressive overload, and how performance is masked by fatigue.

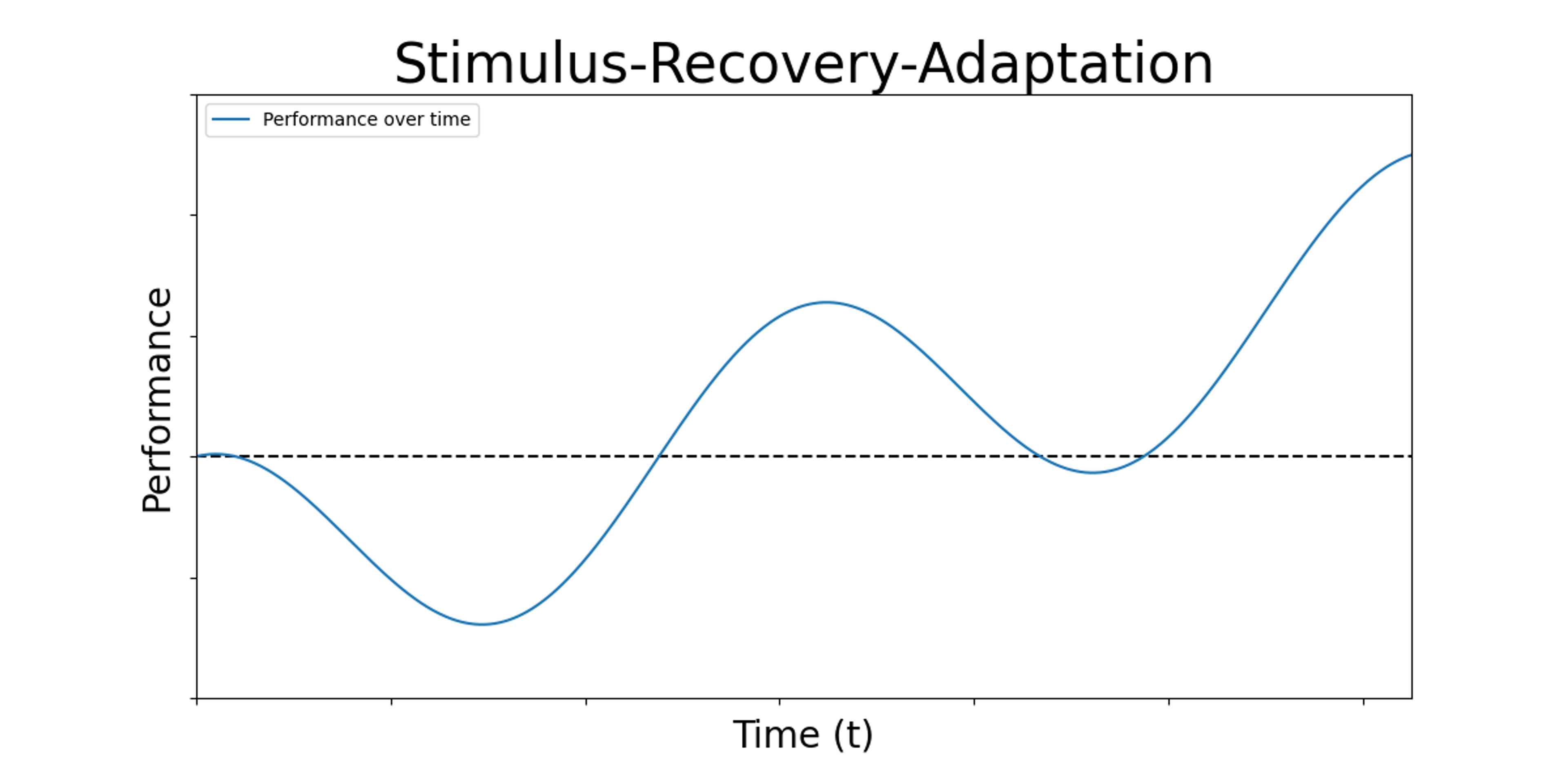

Stimulus-Recovery-Adaptation curve

The first step is the stimulus-recovery-adaptation (SRA). SRA is what we in physics would call a toy model. That is a simple model that captures some features, but not the full picture of reality. However, SRA is a great way to understand how adaptions or getting better at things works. The neat thing is that these ideas generalize to most skills we humans try to learn. It is thus a great framework to describe how you get better at things.

When a stimulus is applied, in our case a training event, it induces stress from which we need to recover. After recovery, we then see an adaption to the stimuli. This adaption is called a supercompensation. We can now repeat the stimulus and over time the adaption increase. However, this also raises a few other cases. For example, we might have too great a stimulus, and repeated over-time recovery demands will decrease performance. Some people would call this overtraining, but that is an entirely different can of worms. The last case is when the stimulus is too small or large to induce a functional improvement and performance flatlines. The first scenario is how most novices will experience training. At some point, we will talk about when this changes, and a more complicated approach may be needed. This is when periodization will become relevant.

The Repeated Bout Effect

When performing the same exercise over long periods with the same weight, technique, or tempo, we keep applying the same stimulus to our bodies. First, the body reacts by adapting to the training with a performance improvement. As a result, we grow stronger, faster, etc. and we will be able to increase the weight on the bar, perform more reps or run faster.

In the ideal world, we would be able to improve our performance this way forever. Sadly, that is not what happens. Instead, as we adapt to the stimulus in the process, we become a little more resistant to that stimulus. The same thing happens for movement patterns and rep ranges etc. This is called the repeated bout effect. The longer we train the more resistant we become to training, this is called the repeated bout effect. To improve further the concept of progressive overload needs to be applied.

Progressive Overload

How do we then keep increasing performance as we adapt to a stimulus? This is done through what is called progressive overload. But what is progressive overload? It entails a few things. In its simplest form, the principle states, that one needs to increase or change the stimulus from exercise over time such that the effective stimulus stays the same.

In practice, progressive overload can be applied in many ways. The different tools might also need to be used over different time scales. Short-term or week-to-month scales the most common way is increasing the load of the exercise, as one grows stronger. But it can also be done by slowing the tempo of reps, pausing reps, performing more reps, or adding more sets. On a month-to-year time scale, one might slowly have to increase the total number of sets done throughout training. For those who get very strong, it might even work in reverse, and one might become so effective at applying a stimulus that training must decrease. Progressive overloading is something that needs to happen in training to improve, simply because we get better. However, this does not mean that the relative effort of the training must increase, only that our absolute performance must increase as our ability to perform increases. When we get to autoregulation, we will talk more about how this is best done in training.

Fatigue-Fitness model

We will now talk about the final theoretical piece before coming to some practical applications. We move to the fatigue-fitness model to get a fuller picture of how increasing performance works. The fatigue-fitness model states that on a given day our performance is given by our fitness fatigue subtracted from our accumulated adaptations. This means that on a given program our performance will tend to increase as long as our fitness adaptations outpace our accumulated fatigue. Due to the repeated bout effect, this also means that if we employ a strategy where fatigue is accumulated over time, then at some point we either have to lower systemic stress or at least change the stimulus for us to keep seeing progress. We will go more into depth on this topic when we get to topics such as periodization, deloading, and the phasic structure of training in general.

Practical application

How do you implement this into your training? The main point of this article is that over time you should see progress in your training. If this is not the case, you are not very surprisingly, doing either too much, too little, or the wrong thing. The strategy of how this progress is applied depends on the programming style. It usually varies from partial to fully autoregulated progress. If your program is fully autoregulated you will usually increase weight/reps etc. as you improve performance. Here you might increase weight this weak if the warmups felt lighter than the last week to keep the intensity the same. Another strategy is the more traditional approach, where a program starts from a 1RM (one rep max) test or something similar, and a predetermined number of reps or weight is then added each week. Finally, we have the middle ground where the first-week weight and reps are selected from the perceptions of effort using RIR or RPE, and then weight, reps, or even RPE/RIR is increased in a predetermined way.

None of these approaches are necessarily better, though some amount of autoregulation like RPE is usually both more favored and modern. However, some personality types might not do very well with this kind of autoregulation. Usually, that goes for people who are either overly aggressive or timid when selecting weight. However, it should be noted, that the ability to autoregulate training is also trainable.

About Rasmus

Powerlifter and coach with more than 7 years in the game.