We have all been there you go to the gym with some planned number in mind that you think you can, should, or want to hit that day. But during the warm-up it becomes clear, the targeted weight will either be way too light or much too heavy. What do you do? Diverge from the programming and get those glorious extra kgs on the bar? Or worse lift the weight even though it is way too heavy and accumulates unnecessary fatigue. No matter what you do you have sinned by diverging from the program.

What if I told you there is a better way? A way to take what is there and leave what is not. That way is called rating of perceived exertions (RPE). It allows you to match your training with your current ability to perform on any given day.

The history of RPE

In 1982 Borg introduced his scale of perceived exertion, also known as the Borg scale. The purpose of the scale was to rate how hard a bout of activity is. Where 6 was no effort at all and 20 was maximal exertion. The focus of the scale was aerobic activity and medical uses. Around 2005, world champion powerlifter Mike Tuchscherer of Reactive Training Systems figured out that such a scale could be useful when lifting weights. This resulted in what we now know as Rate of Perceived Exertion, RPE for short, and is a centerpiece in the trend of autoregulation that has hit the resistance training sphere in the last few years. The purpose of autoregulation is to better tailor training to the individual and allow them to make the maximal possible progress no matter their current life circumstances. This is a stark contrast to the hardcore gym rat culture of old where harder was always better. Even though old culture has its charm the more intelligent approach has its advantages.

What is RPE and why should you use it?

How does RPE work? After performing a set you simply ask, how many more reps could I do? If the answer was 0 the RPE is 10 (@10). If you had 1 rep left it was RPE 9 (@9), 2 left RPE 8 (@8), etc. This may sound simple and it is in principle. But is it accurate one might ask? That is a valid question since novices might not accurately be able to access their effort during exercise. However, this does not matter.

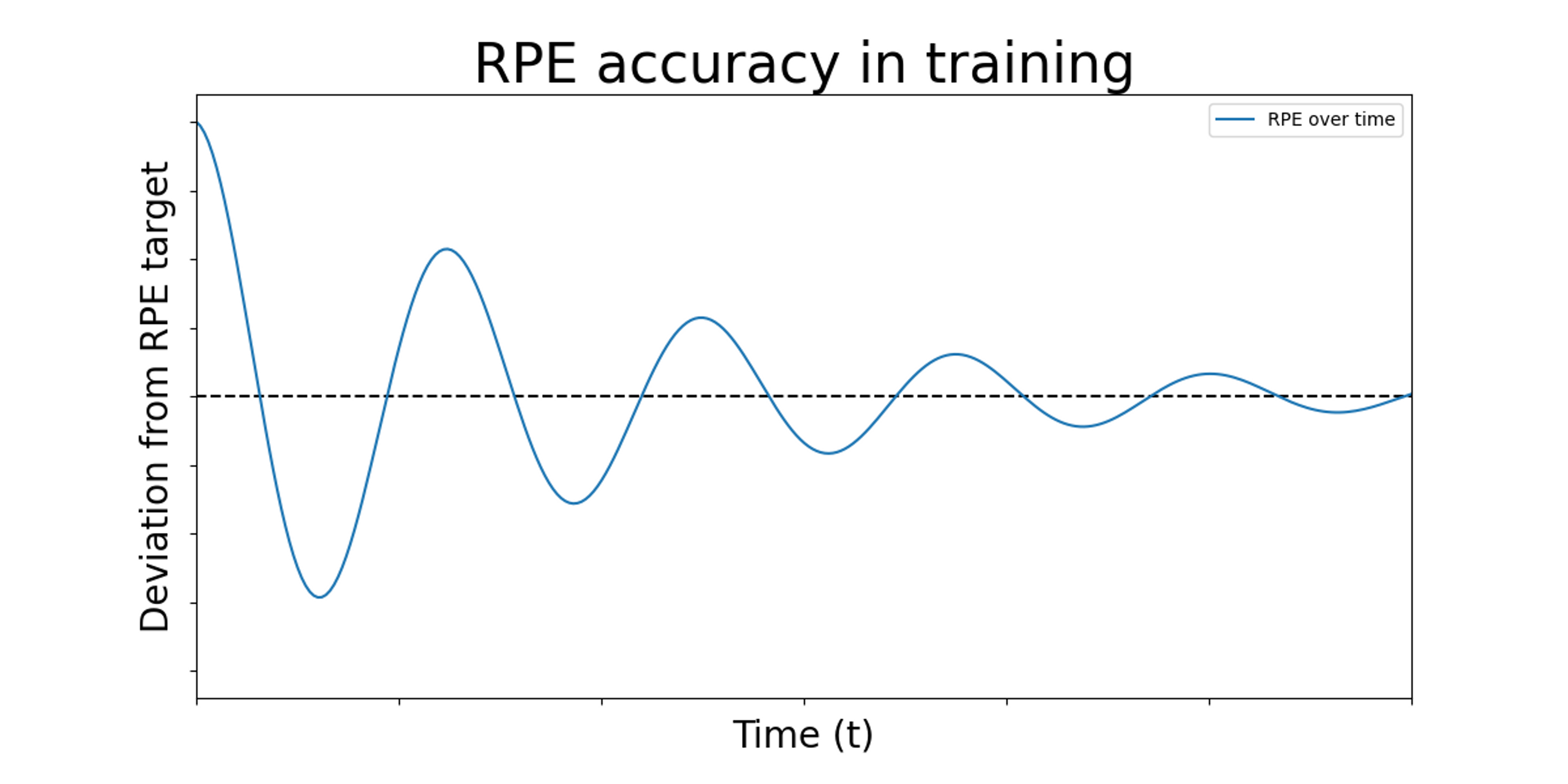

Miss-gauging the RPE in a single training session is simply of very little importance in the long run. Training is not a single event, but the accumulated results of months and years of effort. Over time one will become better at gauging RPE, and the measure will become more and more precise. Meanwhile, one can feel reassured that RPE is still better than the alternative and traditional way of finding out what to lift. That is starting a program with a 1RM test and then planning the next 12 weeks from that point. Such a measure is only accurate on the day of the measurement and only for the rep range tested. Unless some form of autoregulation is employed. When autoregulation is employed, why bother with the 1RM test outside of ego satisfaction or competition?

Now how do you start using RPE in your training? You do not have to commit to RPE on the first day of using it. But when you finish a set, ask yourself, how many reps more reps could I have done? And then assign the set an RPE. Over time your ability to gauge RPE and its accuracy will increase. There are many ways to utilize RPE in programming, and it is a tool that allows one to obtain the intended amount of stress and stimulus from a given program. Which in turn allows one to optimize long-term progress.

Is RPE for everyone?

Ideally, everyone should be able to gauge RPE. I honestly believe RPE is a skill that should be practiced from the start of a training career. However, some types of people do better or worse with autoregulated programming. The person who thrives the most with autoregulation is probably someone who is calculated aggressive, and self-motivated. That is a person that seeks to improve, but not in a relentless way. At the same time, overly aggressive people will probably have to lower their RPE targets. I have one friend who is a very aggressive and emotional lifter. He enjoys amping himself up to become emotionally stimulated when he lifts. This type of training can be very beneficial when one needs to perform, but it also comes at a higher fatigue cost. Such a person should probably lower RPE targets.

On the other end of the spectrum lies the overly timid lifter. One has to seek progress for RPE to work. If someone feels out the weight and doesn't try to progress the system might also not be beneficial. Such a person might have to increase RPE targets or incorporate planned progress to get better over time.

Try our RPE calculator here.

About Rasmus

Powerlifter and coach with more than 7 years in the game.